Bug Bounty 101 (a triager’s perspective)

Bug bounties (BB) are rapidly becoming an essential part of the modern security toolkit for most companies. And for good reason, they provide a cost effective way of exposing your application to a potentially vast range of experts and catch security holes that would otherwise take time and effort to find.

From experience unless you have a dedicated team working full time on security, most bugs uncovered by internal teams are done so in a serendipitous way. Regular pentests are useful for improving security controls and provide that extra compliance check but I find that results are often limited especially when it comes to application security and business logic bugs.

I will share some tips and tricks I learned while handling a bug bounty program for a mid size startup. Most of these tips will apply whether you are using a managed bug bounty platform or implementing and hosting your own program. Platforms like HackerOne or Bugcrowd take care of the boring parts, so if your team can afford it then great. But with the right processes in place, I believe owning your own bug bounty program can be a rewarding experience.

Rules of engagement

First things first, you will need to define a clear set of rules and guidelines so that bounty hunters know which kind of bugs to care about and which ones to disregard. Alignment between the internal security team and bounty hunters is important as it avoids time waste on both sides.

Typical rules of engagement should include things like:

- rules regarding tester identifiers: account name pattern, user agent, request headers

- potential restrictions on the amount of request per second with automated tools

- a general code of conduct

It is also good practice to have a safe harbor policy. A safe harbor is a set of guidelines or rules with the purpose of protecting security researchers or ethical hackers participating in the program. Bounty hunters will feel safe in reporting potentially damaging vulnerabilities without fearing being subject to legal action by your organization.

Also include some generic recommendations to testers. This will help less experienced testers up their reporting game and help you as a triager by reducing the amount of noise. Some examples of good recommendations could be things like:

- asking them to provide detailed submissions with steps on how to reproduce the issue.

- asking them to explain the impact of the security issue. This is actually quite crucial as a lot of bounty hunters approach a bug bounty as they would a regular pentest (maybe because most of them are pentesters?). Ask them to describe the real business impact of a potential vulnerability. Reporting on an isolated security control issue without real impact won’t matter to you, but being able to chain different security issues in a way that affects the crown jewels of your business is highly relevant.

- asking them to follow a responsible disclosure policy (do not post on social media for example).

- asking them to avoid affecting other users’ accounts or PII, they can create different tester accounts to test for access control issues for example.

Scope

Every bug bounty program should have a clear scope listing all the types of systems, assets and applications that are eligible for testing. As such the scope will typically include a list of domains, subdomains, api endpoints or executables that your organization wishes hackers to take a look at. By definition all other assets related to your organization are out of bounds.

The scope should also include a set of restrictions related to the type of security issues that should not be reported upon. This is very important otherwise you will get a lot of reports about things you don’t care about. From experience even having a clear scope sometimes doesn’t stop security researchers from submitting on out of scope stuff. It can be quite annoying and time consuming from an internal perspective but comes from good intentions most of the time IMO. That is one of the big advantages of managed platforms btw, they sort through the noise for you and allow you to focus on the more interesting and relevant submissions.

Common themes that are usually out of scope in BBs:

- Attacks that require physical access to victims device, MIM attacks or compromised accounts

- Social engineering

- Denial of service (DOS)

- Outdated or vulnerable software without POC

- Missing headers or cookie flags

- Brute force attacks

- User enumeration (reset password feature leaking information about user existence)

- Fingerprinting (leaking software versions)

- Theoretical attacks (security controls, unless chaining of several problems leads to a realistic attack)

- Security best practices violations (password complexity, missing security headers,…)

- Leaked credentials (tokens, passwords from Dark Web)

- Rate limit bypass

- Email spoofing (SPF, DMARC, DKIM)

- In general any security problem that the company is already aware of and doesn’t whish to get more submissions about

This list should be customized depending on the specific needs of your organization, and updated regularly.

Bounty payment amounts

I don’t think I need to explain that handing out financial rewards is a powerful incentive that will allow you to attract more security researchers both in terms of quantity and quality. That said, if you’re a small startup and are not ready to give out cash yet, you can still attract more inexperienced hunters looking to improve their skills. This will allow you to build a tight knit community of researchers that you can reward later down the road when you can. You can also give out SWAGs as rewards.

I don’t believe you need to have a clear and public compensation matrix if you are a small to mid size organization, researchers will usually be happy if the retribution is not too far off what would be considered fair for the type of bug found. It is entirely at your discretion on how much you want to give out for which type of bug, although some sort of process internally is desirable to avoid wild fluctuations in the cash amounts given. Consistency will send a clear signal to researchers that you can be trusted to give fair compensations within the range your team has decided upon.

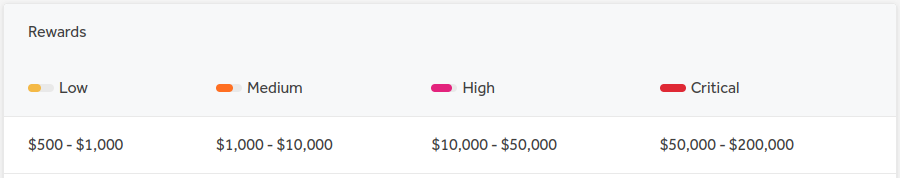

If you do decide to go for a public matrix, the most common pattern I’ve seen is to categorize bugs according to their severity and impact to the business and give out increasing sets of amounts according to these categories. Common classes of bugs are: informational for very low impact bugs, low, medium, high and critical. These categories are based on the Common Vulnerability Scoring System (CVSS), an open standard for assessing the severity of vulnerabilities. They can also be combined with different asset tiers, as such a high impact bug submission could be rewarded differently depending on whether it affects domain A or B.

Shopify’s compensation matrix

Shopify’s compensation matrix

On the inside

Internally you should have a small security champions team taking care of the program. It doesn’t need to be a dedicated security team composed of cyber security experts, although it helps to have a few of those. A purple team composed primarily of developers, devops and some less technical product or operations employees is ideally what you want. These people will be responsible for answering bounty hunters, triaging security bug fixes and potentially dispatching these to specific teams or implementing the fixes themselves.

You do not have to answer security researchers right away, but do not take too long so as not to discourage them from continuing the program with you if they don’t get enough feedback in a reasonable amount of time. One week to at least acknowledge their submission is a good higher bound imo. As long as you regularly give feedback and reassure them that their submission is being looked at, they will feel respected. Most researchers know that organizations have some amount of inevitable inertia in their internal processes and other switching priorities that might add some extra delay in handling bounties.

To save you time, here are a few tips in no particular order:

- have a clear and defined process internally to streamline NDAs and payouts

- use a shared email alias security@mycompany for improved visibility among team members

- use a set of emails templates for common responses to researchers for duplicates or out of scope reports

- regularly refer to your scope and rules and engagement when answering bounty hunters in order to justify rejections

- organize a team rotation within your security champions team so as not to overload members with too much work

Regarding scope, it can be tempting to keep adding more and more restrictions regarding types of vulnerabilities in order to reduce noise, but it can be counterproductive and discourage researchers from reporting classes of bugs that were not in your initial threat model and that actually might have a higher impact than you thought.

I think that goes without saying but be respectful towards bounty hunters and in turn expect respect from them. Do not tolerate abusive speech and threats, don’t hesitate to blacklist researchers that infringe on your code of conduct and the broader set of ethical hacking guidelines.

After you answer and potentially pay the bounty hunter try to handle the bug fix in a timely manner, otherwise other than having a security hole in your infrastructure you might also end up with a lot of duplicate reports. You do not have to reward duplicates, it is a well known and accepted fact among security researchers but it will still take you some time to filter through those.

Once a year do a retrospective of the program, compile a few statistics on the number of bugs found and fixed, as well as the rewarded amounts. This will give better visibility to stakeholders about the program and highlight its potential benefits.

That’s it, I hope you found this content informative. Leave me some comments if you feel I forgot something important or want to share your own experience handling your bug bounty program.